All three major food groups, carbs, fats, and proteins, affect your glucose.

Discounting fiber, Carbs have the most critical impact on glucose. Because carbs break entirely down to glucose, you use your CarbF or an insulin-to-carb ratio (ICR) on an insulin pump or bolus calculator to cover them.

For example, if your CarbF is 1 unit per 10 grams of carb and you eat 100 grams, a 10 unit bolus should cover the meal. Assuming the basal rates or long-acting insulin doses are correct, an accurate carb count combined with an accurate CarbF will control your post-meal glucose. Carbs digest considerably faster than insulin starts to work, so it helps to bolus 15 to 30 minutes before most meals.

Proteins affect post-meal glucose levels with substantially less impact over about 6 hours. Up to half of a meal’s protein content gradually converts to glucose. For adults, meals with 20 grams or more of protein (10 grams or more of carbs) may require an increase in the insulin dose for a meal.

The quantity and types of Fat in a meal determine how many inflammatory particles are generated afterward. This post-meal inflammation rapidly creates insulin resistance strongly associated with developing heart disease. It also necessitates extra insulin for that meal.

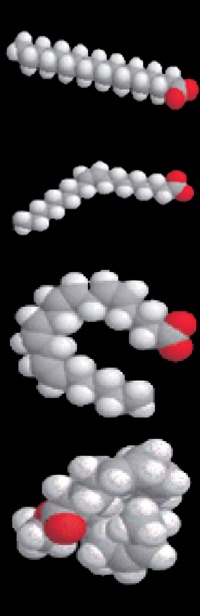

Fats differ significantly in their impact on post-meal glucose levels:

- Saturated fats (1st one), especially palmitic acid, found in meats, eggs, and some dairy products, and stearic acid, found in cheese, sausage, bacon, and pizza, tend to be inflammatory and cause insulin resistance. These fats raise the glucose about 5 hours later and make it harder to bring it down.

- Monounsaturated fats (2nd one) like those in olive oil, avocados, nuts, and natural peanut butter have little or no impact on the insulin dose required for a meal.

- Polyunsaturated fats (3rd one) in vegetable oils can be pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory.

- Omega-3 fats (4th one) from fish and seafood are anti-inflammatory, i.e., they won’t raise and may lower your insulin dose. Be careful with any sauces, though.

- Heating fats can oxidize (damage) them. Meats contain proteins that, when heated, form advanced glycated end products. Both processes can generate inflammation.

Higher fat meals often require meal boluses doses to be altered in size, timing, or type. Because the need for an increase in insulin varies widely for different fats, a formula, like a CarbF, does not work well for high-fat meals. Determine your coverage for these meals by how particular they affect the glucose on your CGM. A CGM lets you see how various meals with more fat and protein affect your glucose.

Keep a record of frequent meals, and the combo boluses you try to find one that best covers the carb portion first and the fat and protein portion over time. Due to their inflammatory nature, avoid meals that send your glucose higher than expected based on their protein and carb content.

Pizzas and other high fat and protein meals raise the glucose higher, later, and longer than its carb content alone. Suppose a pepperoni pizza makes your glucose rise high, bolus early for the carbs, and give a delayed bolus to cover the fat and protein. High fat or high protein meals often require larger bolus doses, mainly when a meal contains more than 20 grams of fat or 25 grams of protein.

As a rough guide, try a 25% larger bolus for pizza or other high-fat meals than that required by the carb count. Cover the carbs right away and give 25% extra as an extended bolus over 2.5 hours to cover the fat and protein.

The 25 Rule for High Fat/Protein Meals

Try a 25% larger bolus than the units required to cover the carbs (1.25 x the carb bolus). Take 75% of the bolus right away for the carbs, and the other 25% in a combo or dual wave bolus over the next 2.5 hours.

Let’s say you need a 10-unit bolus for the carbs in a combination meal. You would multiply the 10 units by 1.25 to get 12.5 units as the bolus. Deliver 75% as an immediate bolus and the other 25% as a delayed bolus over 2.5 hours to cover the fat and protein.

Experiment until you find the right bolus for food you prefer to eat but that raises your glucose more than expected. Again, the healthiest approach is to avoid foods that you suspect generate unexpectedly high glucose readings through inflammation.

Wrapping it up

At first, getting the hang of glucose control on a pump, an AID, or multiple injections often seems difficult. Don’t let this stop you from making small changes to your settings to improve your control. Success only comes from attempts.

The key to great control comes from identifying the factors that positively or negatively impact your glucose. Test each one, one at a time, to identify sources for trouble. Navigate back to calm waters and happy sailing. Diagnose glucose issues faster and learn the steps you need to correct your course. With some effort and today’s tools, everyone can improve their glucose readings.

Where did this equation come from? Do you have a source or article for it?

Thank you for the question, Christina. The link above for “Higher fat meals” leads to an excellent article by Ewa Pankowska, MD, PhD, who has done much work in this area.

I derived the 25 Rule from my clinical experience with patients. You can find it on page 122 in the 6th edition of Pumping Insulin. It offers a relatively conservative approach for handling higher fat and protein meals that, from experience, raise the glucose more than expected.

Love all your books Thank you!!! and her method for bolusing is something I have looked into. I have reached out to her years ago and she was so informative

Thank you!

What about if your meal is high fat and/or protein but no carbs? Would, say, a large plain steak or fish by itself require any bolus?

Hi Mike,

Even with no or few carbs, certain meals may need some insulin. Proteins break down gradually with up to half of the grams of protein gradually converting to glucose over a few hours. A bolus extended over 3 hours might help for a steak, for example. The animal fat in a steak will generate some insulin resistance and this often necessitates an increase in the bolus delivered over time or a delayed bolus or injection.

Vegetable fats, like an avocado, do not cause insulin resistance nor need a bolus.

John

Hi John, How would you recommend blousing for a bag of Quest Protein Chips with 20g protein, 4.5 g Total Fat (0.5g saturated), and 4g Carb? My ICF is 10. I don’t know the formula for figuring out protein plus fats. I’m T1D x 49 years, almost age 60. Pumping insulin. Thank you.

Hi Chris, your CGM is always the best guide for boluses. As a guide, the 4 grams of carb get covered by 0.4 U, of course. For protein, less than half of the protein is slowly converted to glucose over 3 to 6 hours. A good trial dose for one serving would be 0.8 U. The Quest Chips contain healthy fats that should not generate any insulin resistance. However, there are concerns about large quantities of whey protein, but a few occasional servings should not be a problem.

I advise people to avoid high protein diets and hope you are not doing this because they significantly shorten lifespans. Best of health and regards, John